This year, we’ve seen quite a few truly significant films on our big screens. Some of them — the second “Joker” or Francis Ford Coppola’s monumental opus magnum “Megalopolis” — received a very different reaction than what their creators had hoped for.

The predicted euphoria and excitement also didn’t accompany Yorgos Lanthimos’ latest film “Kinds of Kindness,” which had only a brief theatrical run and was talked about for just a short while. A pity, really.

This year, we saw all kinds of cinema — from widely promoted Hollywood blockbusters to cinematic masterpieces showcased at film festivals like “Kino Pavasaris,” “Scanorama,” and “The Bear, the Lion, and the Twig.”

As every year, here we present the TOP 10 best films of 2024.

10. „Megalopolis“ (2024)

Postmodernism often sounds like a curse word in today’s context – faded markers of values, skepticism that often turns into belief in absolutely nothing, extreme subjectivism and individualism, Nietzsche’s famous will to power. All of this often leads to madness. Postmodernism is quite a mad affair. It is a disease of our time.

Nevertheless, there are people who like postmodernism. These are ambitious individuals who know their worth, who believe that they themselves can be their own point of reference and thus maintain balance in a state of instability. They think they can avoid going insane even without solid ground beneath their feet.

Is Francis Ford Coppola such a person? I don’t know. But his latest – and most likely final – film “Megalopolis” (Megalopolis, 2024) undoubtedly brims with postmodern ambition. The director is currently 85 years old, a man who should have accumulated not only professional but also life experience. Yet Coppola seems to have plunged into deep contemplation in his old age.

If real life were happening in a school classroom, we could pat the director on the back and praise him for his knowledge of classical and modern philosophy and literature, ancient history, and his ability to weave it all into a film plot. But if we’re not schoolchildren, if we’ve long since finished school, then we expect from a work of art not just a jumble of ideas, but a realization of an idea within a coherent whole.

In “Megalopolis,” it seems as though the director wanted to cram into two hours everything he’s read over a lifetime. As if, with the sunset of life approaching, he wanted to grasp the essence of everything. As if he wanted to write a testament. One so long the scroll would stretch across the entire room.

This film falls under the dystopian genre – that is, it depicts a collapsing future world – and it’s not short on big ideas. From recitations of the Ancient Roman philosopher Marcus Aurelius by heart to Hamlet’s famous monologue on being, from numerous allusions to Ancient Roman history to the reality of modern Trump-era America.

The story’s main character is Caesar Catalina (Adam Driver), a visionary architect of New Rome (resembling modern-day New York). Caesar wants to build a utopian city where everyone lives in harmony and constantly learns from one another. His visions are grand, but his mental state is unstable – he is prone to mania, addicted to drugs, and has suicidal thoughts. And… he can stop time. Caesar is like Coppola himself – the great director who can sacrifice everything for the sake of an idea (back in the ’80s Coppola nearly went bankrupt because of the film studio he founded), who, like a Deus ex Machina, watches the world from his balcony box as if it were a film set.

Caesar, of course, has his opponents – the mayor of New Rome, Cicero (Giancarlo Esposito), who, although unable to win the sympathies of his voters or manage the city, has a more grounded outlook and doesn’t believe in grand utopias. The journalist Wow Platinum (Aubrey Plaza), abandoned by Caesar, desperately tries to regain his attention, but when kindness fails, turns to dirty tricks. Caesar’s cousin Claudius Pulcher (Shia LaBeouf) tries to win over the crowd and seize power, jealous of Caesar’s talent and influence.

There are also supporters. Julia Cicero (Nathalie Emmanuel), the mayor’s daughter, falls in love with the great architect for his grand ideas. Uncle Hamilton Crassus (Jon Voight) supports him financially. The loyal aide Fundis Romanus (Laurence Fishburne) drives his boss everywhere, gets him out of trouble, and narrates his story with the voice of Herodotus.

New Rome itself resembles a city of sin, where wild bacchanalia are constantly held, and at the same time there exists a cult of vestal virgins – both artificial and primitive, because in New Rome, you are what you desire. Politics equals entertainment. Economics, journalism, and sexuality – these are the three foundational pillars of the city of sin, as Caesar states. The masses need bread and circuses. Culture, journalism, and politics in New Rome are a circus. The city is perpetually for sale. Everyone can be sold for money, power, or fame – and can even sell themselves.

On the other hand, Caesar Catalina speaks of a different reality – a utopian one. He speaks of love and freedom – for those who love, there is nothing to fear. Remembering his deceased wife, Catalina finds inspiration for new visions.

All the character names immediately reveal allusions to Ancient Roman history, to a Shakespearean reality that itself often drew from antiquity. Coppola borrows from Shakespeare the contrast between beauty and ugliness – but he does not idealize beauty. Just as Shakespeare didn’t. Postmodernism in this film becomes apparent particularly in the power games, temporary values, and especially in the film’s form, as “Megalopolis” is Coppola’s experimental creation. The visuals flood the consciousness with force, all at once and intensely, while the abundance of ideas makes it difficult to find a common denominator. (Dora Žibaitė)

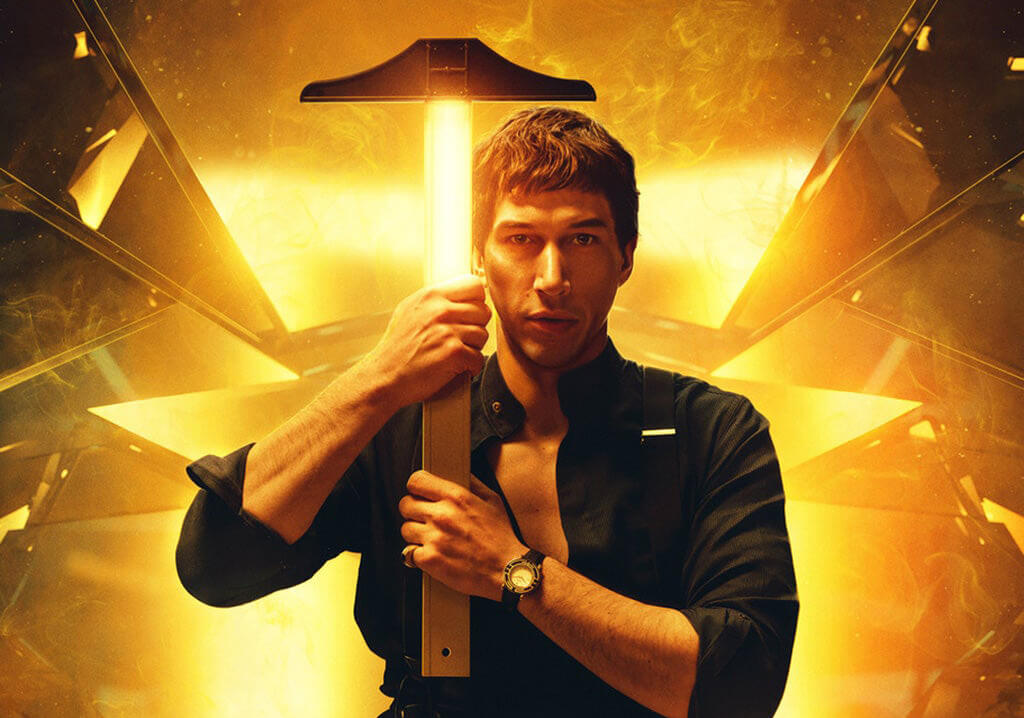

9. „Monkey Man“ (2024)

A film pulsing with the roots of Hindu mythology and the vivid shades of Mumbai’s streets, “Monkey Man” is a bold directorial debut from Dev Patel – a brutal and thrilling exploration of revenge, identity, and redemption.

The film unfolds against the backdrop of a city marked by a stark divide between the wealthy elite and the impoverished masses. Kid (played by Dev Patel himself), a shadowy figure hiding behind a gorilla mask, drifts through the brutal world of underground fight clubs, where every punch is a desperate attempt to survive. Having suppressed his anger for years, he discovers a way to infiltrate the circles of the city’s menacing elite. Haunted by childhood traumas that resurface as he moves closer to his enemies, Kid sets into motion a merciless plan to take revenge on the men who took everything from him.

Dev’s character, Kid, embodies an intriguing narrative choice that speaks volumes about his journey and the film’s central themes. The name Kid, or rather the absence of a traditional name, plays a crucial role in understanding his character and the broader story. Kid’s anonymity becomes a metaphor for the faceless, nameless, and marginalized existence within society. By not giving Kid a specific name, Patel turns him into a symbol of every person fighting against oppression and injustice. This choice resonates powerfully in the film’s narrative context – a society sharply divided by wealth, power, and class – highlighting the dire circumstances of those often overlooked or silenced by the forces of corruption and elitism.

Patel, known for his roles in “Slumdog Millionaire” and “Lion”, reinvents himself in this film created in collaboration with visionary producer Jordan Peele, merging his storytelling with the neon-lit, morally ambiguous landscapes of contemporary India. “Monkey Man” is not just a tale of personal vengeance, but also a sharp critique of social stratification and the entrenched corruption within it.

Inspired by the indomitable spirit of Hanuman – the revered deity symbolizing strength and loyalty – “Monkey Man” plunges into the psyche of a young man haunted by a traumatic past and consumed by an insatiable hunger for justice. His scarred and mysterious hands become tools of chaos as he launches a meticulously planned crusade against the city’s powerful syndicates. With each defeated enemy, his journey transforms into a broader examination of society’s ailments – corruption, exploitation, and the chasm between the rich and the poor.

Hanuman’s role as protector and bestower of power aligns with Kid’s mission to confront the city’s elite oppressors. The film also portrays the hijra community – India’s historically marginalized third gender – and Kid’s alliance with them, creating a parallel with Hanuman’s compassion and respect for all beings. This highlights themes of solidarity and the fight for dignity and recognition of marginalized communities.

In his directorial debut, Dev Patel chooses not to include hijras merely as background characters, but instead positions them as central figures in Kid’s journey and the film’s thematic tapestry. This decision reflects Patel’s intention to challenge and redefine societal norms by shining a spotlight on a community long pushed to the fringes. By giving hijras roles that are integral to the protagonist’s mission to overthrow the corrupt elite, “Monkey Man” emphasizes their resilience, strength, and the injustices they endure. The film’s depiction of the hijra community goes beyond symbolic LGBTQ+ inclusion – it’s a deliberate effort to humanize and elevate their identity, showcasing their courage in the face of adversity. Their inclusion underscores the necessity of solidarity among all marginalized groups, especially those historically silenced or oppressed.

The film’s aesthetic, blending brutal realism with stylized violence, draws inspiration from the frantic energy of Indonesian action cinema, particularly reflecting the intense pace and psychological impact of films like “The Raid.” Patel, as director, ensures that the fight scenes are not just displays of physical prowess but expressions of the protagonist’s inner turmoil and relentless drive for revenge.(Gabrielė Plikynaitė)

8. “The Convert”, 2024

Let us recall the cultural shock we experienced watching the masterpiece “The Piano” (1993), directed by Jane Campion and awarded three Oscars as well as the Palme d’Or at Cannes. Shot in New Zealand, the film introduced most viewers for the first time to the indigenous Māori people of this green continent and their ancient tradition of facial tattooing.

In 1994, New Zealand director Lee Tamahori’s film “Once Were Warriors” caused a real sensation at the Venice Film Festival, depicting the descendants of old Māori tribes struggling to survive in a modern urban hell.

The film’s success catapulted Tamahori to Hollywood, where he went on to direct the gangster thriller “Mulholland Falls” (1996), the brutal survival drama “The Edge” (1997), a James Bond installment “Die Another Day” (2002), and a handful of other American-standard productions (including one episode from season three of “The Sopranos”). Eventually, however, he returned home. It was there that he created “The Convert”, once again delving into Māori themes.

The year is 1830. The edge of the world. A British ship anchors off an island in the Tasman Sea, home to an indigenous Māori tribe. The newcomers bring massive loads of gunpowder and weapons. But the British have not come to wage war – they’re here to trade their goods for timber and food. How the locals will use the weapons and gunpowder doesn’t interest them. In fact, they secretly hope that if rival tribes begin to fight each other and thin their own numbers, British leadership will be all the more pleased.

Among the British sailors – dubbed the “merchants of death” – is former soldier Thomas Munro (played by Guy Pearce), now a preacher seeking redemption for past sins. No sooner has he stepped ashore than he witnesses a shootout between locals. Just having obtained weapons, members of one tribe are quick to settle old scores with another.

Munro rescues a girl named Rangimai and takes her with him to the British settlement of Epworth. He is expected there – the church has been inactive without a priest, and even a house has been built for him. When Munro moves in with the girl he saved, the townspeople are far from pleased. Most of them believe the Māori are savages.

Soon, the events of the near future reveal that the real savages are not the indigenous people but the colonizers in tailcoats, sipping milk tea, proudly proclaiming their heritage and loyalty to the British Empire.

There’s no doubt that “The Convert” will remind many of Mel Gibson’s “Apocalypto.” That film depicted 16th-century Native Americans, with dialogue translated into the exotic and unfamiliar Mayan language. Its core was based on events from 500 years ago, when the Spanish army conquered Mexico and Central America.

“The Convert” takes place in a different corner of the world, yet the conflicts between civilizations are surprisingly similar. (Gediminas Jankauskas)

7. “Heretic”, 2024

“Heretic” – (Latin haereticus < Gr. hairetikos – sectarian Plato (Plato; 427-347 BC)) – a confessor, proclaimer of heresy; a deluder, an outcast.” (Dictionary of the Lithuanian Language)

Heretic (2024 in the film industry) – the charming rom-com veteran Hugh Grant, that is, the nameless heretic Mr. Ryd in A24’s latest release “Heretic”, attempts to save the world from religion like some sort of Marvel hero, converting Good Samaritans to atheism. Or maybe… not?

As in life, this film leaves room for doubt – unsurprisingly, it tackles religious themes and presents two opposing sides of the barricade. On one side, deeply devout (or maybe… not?) Mormon girls, and on the other – a deeply non-believing (or maybe… not?) atheist.

Honestly, I expected the usual atheist staple: logical resistance to the doctrines offered by religion. And yes, I got that. But I also hoped that maybe, this time, the arguments would shake me, maybe my faith (or lack thereof) would waver. Maybe the atheists would say something new?

But alas – there is nothing new under the sun. Hugh Grant, with his charming smile, witticisms, and good humor, simply sang the old, well-known tune: “religion is a tool to control the masses.” His opponents, two young Mormon missionaries who show up at his home to bring the lost sheep back into the fold, repeated the other familiar refrain – “no no no.” Neither side surprised me.

It’s worth noting that this is a horror thriller. Half the film, I wasn’t sure whether we’d get full-blown slayings or if Hugh Grant would remain the gentleman philosopher, pondering life’s big questions. But yes – there was blood, and the kind of brutal elements typical of horror-thrillers. Despite some completely implausible and absurd moments (not in terms of real-life believability, but even in the film’s own logic), everything was told with a straight face – fake it till you make it – and it still managed to grab and hold attention.

That success is due to a few factors. First of all, the idea to write a horror script about Mormon girls encountering an atheist trying to “sell” his belief system (not believing in God means believing there is no God) is simple but brilliant. Directors Scott Beck and Bryan Woods took a risk by diving into the topic of religion, but another key to their success – they didn’t offend anyone. Somehow, they managed to walk the fine line: both faith and non-faith are presented respectfully (maybe slightly leaning toward the faithful, though the atheist side gets its justifications too).

Another strong suit of the film – the dialogues and characters. The characters are clear, vivid, and their contrasts spark compelling conflict. And let’s be real – it’s always interesting to hear the arguments: Why is religion not worth believing in? Why is it? Who’s lying? Who’s telling the truth? Politics and religion – the two most fascinating topics that ignite the most passion in human hearts.

A24, known for its horror films, tends toward religious and psychological themes. Other well-known A24 films with similar subject matter include “Dream Scenario” (2023), “Beau Is Afraid” (2023), “Midsommar” (2019), among others.

Directors and writers Beck and Woods have said that “Heretic” was inspired by the 1997 sci-fi film “Contact” and the 1960 courtroom drama “Inherit the Wind”, both of which explore religious themes in a way that’s “like munching on popcorn” – a little cheeky and light, without overloading the brain with theological heavy lifting. And that’s exactly the vibe while watching – theology was definitely not the main focus. First and foremost, it’s entertainment – just different enough to be even more interesting. (Dora Žibaitė)

6. “The Kinds of Kindness”, 2024

Yorgos Lanthimos is a well-known name in the world of cinema. This Greek director has amazed film lovers with strange and eccentric works like the recently released Poor Things (2023), the earlier The Lobster (2015), The Killing of a Sacred Deer (2017), and others. Some viewers call his films mindf***s and leave the cinema asking “What did I just watch?”, while others walk out enchanted, stretching a long “woooow.” Yorgos hasn’t slowed down, and this year, he brings us yet another creation born of his vivid imagination – Kinds of Kindness.

An interesting fact about Yorgos – he likes to work with the same team. In this project, he continues his collaboration with Emma Stone, Willem Dafoe, and Margaret Qualley, all of whom starred in Poor Things. This time, he also added Jesse Plemons to the main cast. The screenplay was co-written with his longtime creative partner Efthimis Filippou, with whom he previously worked on The Killing of a Sacred Deer, The Lobster, and Dogtooth (2009).

What’s unique about Kinds of Kindness is that the film isn’t one continuous story, but three one-hour narratives that are unrelated plot-wise, although they feature the same main actors. Once the film was released, many viewers tried to decipher what connects these three miniature films besides the repeated cast. Since they’re packaged as one whole, surely there must be a common denominator? Yet many were left scratching their heads trying to find it.

The first story revolves around Robert (Jesse Plemons), a corporate employee who is more like a slave to his boss Raymond (Willem Dafoe), obeying his every command down to what to eat, what to wear, how much to weigh, when to have sex with his wife, whether to have children or not. The director takes an intriguing approach by not revealing everything right away – the audience has to slowly unravel the story and figure out how the silent bearded man R.M.F., the young woman in the short robe, and the suited man trying to run over the bearded one are connected. Robert’s final straw comes when Raymond commands him to kill someone. When he refuses, he falls out of Raymond’s favor – and the detective-style chase to regain it begins.

The second story is even weirder. Daniel (Jesse Plemons) is a police officer whose behavior turns strange after his wife Liz (Emma Stone) disappears. He starts seeing her face in criminals, wants to watch an old group sex video with her in it (while she’s still missing), and gets frequent silent phone calls. One day Liz suddenly returns – but Daniel doesn’t believe it’s really her. A psychiatrist diagnoses him with manic depression and prescribes medication, but Daniel’s paranoia persists. He’s convinced the woman living in his house is an impostor.

The third story follows a sect that has chosen a few of its own as divine figures – only they can be touched, only their tears can be drunk, only their theories followed. Emily (Emma Stone) and Andrew (Jesse Plemons) are chosen to embark on a sacred mission to find a girl believed to have healing powers – someone who can even raise the dead. Andrew is your typical cultist: shaved head, baggy clothes, always in sandals. Emily, however, is different – she still has a husband and daughter she struggles to leave behind. When they discover the holy girl is real, and Emily loses the sect’s favor, she desperately tries to capture her.

Yorgos Lanthimos’ Kinds of Kindness feels like a Greek tragedy – perhaps because of the sacred, hymn-like music playing in the background, which is characteristic of his other films as well. His films are not overtly about religion and don’t directly examine questions of faith, but in many ways, it feels like he is trying to understand the role of God, and the relationship between divinity and humanity, through his storytelling. (Dora Žibaitė)

5. “Substance”, 2024

A rising star in the film world, French director Coralie Fargeat has just released Substance (2024) – the new The Shining (1980), only in a female version. Horror, bloodbaths, madness, beauty, youth, old age, death… Fargeat seems to have cracked the modern female psyche and delivers its fractured identity through a dazzling blend of aesthetics and grotesque.

Truth be told, she’s still a newcomer in the film industry. Until now, Fargeat had only directed one feature film, a few short films, and some TV episodes. She also writes all her own scripts. Born in Paris, she studied at one of the capital’s prestigious film schools and was selected to participate in a year-long screenwriting workshop. But the film mentors of that time prophesied her scripts would never make it to screen – claiming they were too visually violent.

And yet, here we are. Not only has Fargeat released her own written and directed film – exactly as brutal as her mentors warned – she also secured major stars like Demi Moore and Margaret Qualley. Substance debuted at the Cannes Film Festival and won the award for Best Screenplay.

Elizabeth Sparkle (Demi Moore) is a faded movie star, now in her fifties. She hosts televised aerobics classes, still watched by fans on their home screens – but ratings are falling. People remember her former glory, but the memory is fading. She lives in a luxury high-rise, financially secure, but entirely alone. Her fans are her only comfort.

Her manager Harvey (Dennis Quaid) makes it clear – a woman her age no longer sells. His show needs a new star – younger, prettier, sexier. Elizabeth listens, eyes wide open, slowly letting the belief sink in that without her youth, she’s worthless.

Then, she gets into a car accident. No injuries. But a young nurse notices her and slips her a mysterious tape titled Substance, telling her it changed his life.

At home, Elizabeth watches the tape. It presents a new drug that allows a kind of rebirth – more precisely, it creates a continuation of your physical self from your original body matrix. A new, youthful, beautiful being. But it cannot exist without its “mother.” Elizabeth is skeptical at first, but the world keeps shoving her face into the idea that the current version of her is no longer wanted. And so, Sue (Margaret Qualley) is born.

Sue is exactly what everyone wants – sexy, a little naive and girlish, but totally in control. And Sue loves her life. She doesn’t want to stop. But there’s one catch to taking Substance: Elizabeth and Sue must switch lives exactly every week.

There are many themes woven into this film, but the central one is self-loathing. Today, we have countless self-help books and motivational videos preaching the importance of loving yourself, putting your own needs first. Yet ironically, in this world so obsessed with self-love, it turns out you’re only allowed to love yourself as society has programmed you to be.

While the leads are Elizabeth and Sue, their manager Harvey plays a small yet crucial role. He delivers lines like, “Girls should be pretty and happy,” “Girls should smile,” and finally, “She’s my greatest creation.” What Elizabeth becomes is Harvey’s creation. Harvey symbolizes the modern cult of youth and beauty – a cult every woman is expected to worship, and every man serves. But contrary to Harvey’s beliefs, beauty and happiness don’t always go hand in hand.

So it’s no surprise that conflict soon arises between what’s beautiful and what actually brings happiness. Elizabeth’s beauty becomes more important than her joy.

What’s more, the film breaks Substance’s core rule – the matrix and its copy are indivisible. They are one and the same. But how can you truly perceive yourself as “one and the same” if half the time your copy is walking the earth without you? Even if she’s younger. Elizabeth starts to lose the ability to distinguish Sue from herself. Though the two never meet, hostility between them begins to grow.

And that’s symbolic. Because in truth, Elizabeth is at war with herself. More than anything, she longs for love. But for someone who hates herself, love is out of reach. And hate is ugly. Rage is ugly. And so, as the story unfolds, Elizabeth’s internal rot begins to show on the outside – gradually, but unmistakably.

This entire farce plays out in repetitions – the kind you’d find in folklore, where the third brother visits the witch three times, and each time something different, yet increasingly intense, happens. Within this structure, we get to watch – up close – how beauty transforms into monstrosity.

4. “Lee”, 2024

Some time ago, we started our review of the excellent military drama “A PRIVATE WAR” (2018, directed by Matthew Heineman) with a horrifying statistic:

“At least 80 journalists have been killed for their professional work around the world in 2018, according to a report by the influential international humanitarian aid organisation “Doctors Without Borders” (MSF).

More than half of them died in five countries – Afghanistan (15), Syria (11), Mexico (9), Yemen (8) and India (6) – according to an MSF report published in Berlin. In total, 702 professional journalists have been killed worldwide in the last 10 years.

Of course, far from all of them get biopics, as was the case with the heroine of “Private War”, Marie Colvin, the British war correspondent for The Sunday Times (inspired by Rosamund Pike in the film), who covered the war from 1985 until her death in 2012. As a war correspondent, this courageous woman travelled to many military hotspots, almost died in Chechnya in an attack by Russian warplanes and lost her left eye in Sri Lanka in 2001. He was killed in Syria in the siege of Homs by artillery fire.

Equally interesting is the biography of Elizabeth Lee Miller (1907-1977), the famous photomodel and talented photographer for “Vogue” magazine and a passionate campaigner for women’s rights. In the biographical drama “Lee”, based on the book by Antony Penrose, the famous actress Kate Winslet gave a performance so convincing that she could be considered the most serious contender for an Oscar.

With war in Europe, Elisabeth takes a job at “Vogue” magazine in London. Her first photographs show that she is talented, but her true abilities will be revealed when she applies for accreditation to go to the front. Soon, she starts sending the editorial office photographs of people maimed by the war, telling horrific stories.

She is credited with the first ever photographic use of napalm on the front line. Li’s lens captured the Battle of Britain in 1941 and the Nazi atrocities at Buchenwald and Dachau concentration camps. And it was she who visited Hitler’s apartment in Munich on 30 April 1945 with “Life” magazine correspondent David Sherman. On the same day that the Führer committed suicide in his Berlin bunker, a famous photograph was taken in his Munich apartment of a nude Li Miler posing in Hitler’s bath.

Rather than continuing to write about the “Truth Shot”, I suggest you read a very detailed article published by LRT:

https://www.lrt.lt/naujienos/veidai/14/2409011/lee-miller-gyvenimo-dramos-seksualine-prievarta-depresija-ir-sunaus-nuoskaudos

Why repeat what has been perfectly analysed by a specialist (G.J).

3. “The Room Next Door”, 2024

This film, which (so far!) crowns the career of the famous Spanish film director Pedro Almodóvar, was awarded the main prize – the Golden Lion – at this year’s Venice Film Festival.

It can be said with confidence that P. Almodóvar’s international career began precisely at the Venice Film Festival, when at the age of 39, he presented his film “Women on the Verge of a Nervous Breakdown” (1988) there, which brought him awards for Best Screenplay and to lead actress Carmen Maura.

Many years have passed since then, during which the Spanish genius refined his style and created 15 more feature films.

Even during the Covid lockdown, he didn’t sit idly by – in 2020, he managed to direct a 30-minute drama remotely, based on Jean Cocteau’s classic play “The Human Voice”, with Tilda Swinton in the leading role.

In 2023, at Cannes, he presented the 30-minute Strange Way of Life, which, according to the director himself, is “a strange Western in the sense that two men love each other.” The lead roles were played by Ethan Hawke and Pedro Pascal.

And The Room Next Door, which triumphed in Venice, is P. Almodóvar’s first English-language feature film. According to The Hollywood Reporter critic Lili Ford, it “was honored with a passionate 17-minute standing ovation.”

The film is based on Sigrid Nunez’s novel “What Are You Going Through”. At a press conference in Venice before the film’s premiere, the famous Spaniard stated, “This film is in favor of euthanasia.” He added: “There should be a possibility to access euthanasia worldwide.”

In reality, euthanasia is still not legally permitted in many countries. But filmmakers often support the idea (naturally, entirely voluntary). We’ve seen the moving Spanish drama The Sea Inside (Mar adentro, 2004, dir. Alejandro Amenábar), awarded an Oscar and many other prestigious prizes, in which Javier Bardem plays a man bedridden for three decades, determined to prove that one can overcome a cruel fate only by asserting the right to leave this world with dignity and of one’s own will.

Three years ago, we saw French director François Ozon’s film (optimistically titled?) Everything Went Fine (2021), which explored the much-debated issue of euthanasia without the typically understandable tragic tones.

Emotional turmoil is also provoked by P. Almodóvar’s The Room Next Door.

This time, Tilda Swinton plays a woman named Martha. Tired of fighting incurable cervical cancer, she wishes to die with dignity and asks her friend Ingrid (played by Julianne Moore) to stay with her and be in the next room when she takes a euthanasia pill obtained illegally.

Martha and Ingrid share a long-standing bond of close friendship and similar professional paths. Decades ago, they worked together at the same magazine. Martha was a war correspondent, while Ingrid, even now, writes popular novels. Her latest work is a book of reflections on the fear of death.

But there’s a big difference between contemplating abstractly about what awaits every human being at life’s end – and actually being present during the agonizing final moments of a loved one.

The friends rent a luxurious modernist house near Woodstock, featuring stunning interiors, and discuss all the crucial details: Martha’s room door (bright red!) will always remain ajar. Except on the day the final decision is carried out.

The Room Next Door bears little resemblance to Almodóvar’s earlier works. Instead of the typically theatrical fireworks of passion and sexual desire – a restrained stillness, and the oppressive wait for inevitable death that fills every corner of the screen. There’s almost none of the humor the director once loved – which, in this context, would be entirely inappropriate.

Only one element of the film is truly “Almodóvarian.” It’s the color in the friends’ temporary abode, which, quite possibly, is meant to evoke the Catholic idea of Limbo (a place for souls not admitted to heaven, but not condemned to hell or purgatory).

It is a magical space, whose symmetry could make even Wes Anderson envious. With him, Almodóvar could also compete in terms of color palette. Some colors are bright and even aggressive; others are pastel and soothing. Everything is carefully considered and aligns beautifully with the emotional states of the two women.

As The Hollywood Reporter film critic David Rooney aptly notes: “Only in an Almodóvar film could you see a hospital patient wearing pajamas in dazzling fire-engine red, azure, and purple – reminiscent of a firefighter’s uniform (all of Bina Daigeler’s costumes are eye-catching).”

Production designer Inbal Weinberg turns each carefully planned interior into a distinctive frame in which we observe the two protagonists…

Even individual details of the space are clearly not random. A reproduction of Edward Hopper’s painting People in the Sun hanging on the wall “rhymes” with a scene in which the two friends lie side by side on loungers, soaking in the sun.

The book spines on the table illustrate the intellectual interests of Martha and Ingrid (and possibly the director himself!).

Cinematic references serve the same purpose – from excerpts of John Huston’s The Dead (based on James Joyce) to a Buster Keaton comedy playing on the TV.

And in one shot, we see a striking citation from Ingmar Bergman’s Persona, showing only half of each woman’s face. But here, this evocative detail emphasizes not a merging of two identities, but a tragic separation.

Tragic counterpoints pierce the soul in the musical compositions of Alberto Iglesias. And the most powerful visual highlight that lingers long after the screening: soft snowflakes of an almost surreal color. Perhaps this is how the world is meant to look in one’s final moments. (G.J.)”

2. “Dune: Part Two”, 2024

Waiting for the third “KOPOS”…

The epic fantasy novel Dune, completed five years later in 1965 by the American Frank Herbert, has long attracted the attention of filmmakers. Unfortunately, the first attempts to turn the cult book into a film were not successful.

Alejandro Jodorowsky, a renowned master of auteur poetic cinema, was the first to do so, but he conceived of the film as a twelve-hour (!) journey through different universes and different cinematic styles. Obviously, this crazy project never materialised due to lack of money.

David Lynch’s Dune (1984), which cost $40 million and was a financial failure, was panned by the critics, but this creative failure was not so much the fault of the director and the actors, but rather of the studio executives, who tightly controlled the project and interfered constantly in the creative process.

There was another attempt to turn the five-part novel into two separate films for television, Dune (2000, dir. John Harrison) and Children of Dune (2003, dir. Greg Yaitanes), but they did not become major cinematic events.

Canadian director Denis Villeneuve’s Dune: Part One (2021), on the other hand, was a big hit with both fans and sceptics of the cult novel. The film was nominated for ten Oscars, won six gilded statuettes and earned three times its cost ($400 million). Which means that a sequel is simply inevitable. And the second part of Dune will hit the screens around the world (including here) in early spring.

And the second film is set in the distant future in an interstellar feudal human empire and tells the story of a space empire’s wasteland that has become the most valuable planet in the future universe.

After losing his father on a hostile and dangerous desert planet called Dune, Paul Atreides, who has settled with the local desert people, the Fremena, makes new friends and finds the love of his life. Together with the beautiful Chani, he is destined to change the future of the planet.

And of course, the desperate struggle will continue, not only against those who murdered Pol’s father and threaten to destroy the Fremen, but also for the planet’s greatest treasure: a special spice, a precious substance that gives those who consume it increased vitality and an expanded consciousness. This invigorating “vitamin” is essential for faster-than-light interstellar travel, enabling space navigators to safely navigate interstellar space.

Already when watching the first Dune closely, one’s breath was taken away by the enormous panoramas in which even characters important to the plot often appear as tiny grains of sand tossed about by the winds of fate.

In the second film, the special effects are given even more attention: the Harkonnen buildings, the Padishah Emperor’s spaceship, and, of course, the giant, all-consuming desert earthworms, one of which is saddled up by Pol, are all worthy of their own conversation.

Hans Zimmer’s very impressive score, which once again astonishes the audience with both majestic volleys of sound and perfect compositions.

The plot picks up just after the end of the first film’s narrative. Surviving miraculously the inferno of the war between the Harkonnens and Emperor Shaddam IV, Pol and his mother Lady Jessica (played again by Timothée Chalamet and Rebecca Ferguson) travel through the desert, accompanied by a squad of soldiers led by Stygar (Javier Bardem).

Paul is driven by his unquenchable desire to avenge his father’s killer, while Jessica, Paul’s mother, is destined to undertake an incredible mission…

In addition to these previously seen characters, a number of new ones appear (Florence Pugh, Christopher Walken, Léa Seydoux, etc.), but they appear briefly and disappear for a long time. It is now clear that they will appear for a longer period of time in the third part, which is already entitled “Dune. Messiah”).

And to keep the wait alive, we can watch the TV series “Dune. Dune: Prophecy” (G.J.).

1. “Civil War”, 2024

Paradoxical as it may sound, the recent release of Civil War in cinemas is like a musical, but it is not a musical – brutal scenes of war dancing on the screen, one after the other, faces lit up in dramatic horror and anguish, while calm indie folk music plays in the background, and in some places colourful details shine through, such as blue and pink paint on the wall, blue and pink nails and hair on the soldiers, blue and pink on the water-sprayed lawn. Horror and laughter, disaster and adventure, action film and musical – seemingly irreconcilable, but that’s exactly what fascinates Alex Garland, the award-winning and multi-nominated director.

Silence and noise in war are perhaps two interesting opponents. There is a terrible noise followed by an even more terrible silence as you walk around looking at dead bodies, car bombs, the ruins of houses. And people do not have the sense to speak, because in the face of tragedy we are mute. That is what first struck me when I started watching the film: the relationship between silence and sound. In the silence, there is only the click of the camera film, because we need to document, because sometimes that is all we can do. But really?

The film is set in a dystopian future United States. Neither the exact future date nor the reasons for the war are given, and the action is centred on a group of journalists travelling through the warring states trying to document the war. Their latest goal is to reach the capital and interview the President, who is nearing the end of his term.

Things could have been very uninteresting and domestic, but things get complicated when Ly (Kirsten Dunst) and Joel (Wagner Moura) are joined by a young woman, Jesse (Cailee Spaeny), and an old journalist, Sam (Stephen McKinley Henderson). Jessie wants to become a good war photojournalist like Ly, who was famous for her big hikes as a war reporter, while Sammy, plump and elderly, is looking for a motor car to help him get to the city he wants to visit for journalistic reasons. Jessie is still very young and has not seen the atrocities of war, and Semi, though a seasoned wolf, is too slow and clumsy.

The screenplay was written by Alex Garland himself, so this is not his first work as an author. He has also made a name for himself with films such as Ex Machina (2014) and 28 Days Later (2002), which also belong to the dystopian genre. Apparently, Garland is at his best when it comes to dealing with problems that have their roots in the present, but whose size and scope will come later.

In The Civil War, it is the journalists who take centre stage. Their aim is to document the war. What is important to know about war journalists is that they cannot intervene in what is happening in front of their eyes, or rather, they can, but then they would no longer be fulfilling their primary mission. The question is: what is more important, saving a man who has been set on fire or taking his photograph so that the whole world can learn about the horrors of war?

So the attempt is made to penetrate the consciousness of a tragic figure. What kind of person is he who must remain indifferent in the face of tragedy? One might say that his aims are noble, but his behaviour is immoral by common standards. Nevertheless, it is generally accepted. And in general, the film tries to hang on to the question of indifference, as if the Americans were trying to react to what is happening in the world, to the extent of our indifference, when in our warm embrace we pretend that nothing is happening. We sell vintage dresses and serve customers while two soldiers with submachine guns stare at us on the roof. It’s a scene from a film.

The director’s answer to this problem is simple and brutal: we are a spectator society. And journalists – yes, they are nobly trying to document reality, in fact they are creating historical material for future generations, but unfortunately a journalist, for other professional reasons, will always be looking for a sensation. And, by way of contrast, Garland shows that there are not only independent journalists, but also biased journalists who take sides in order to get some benefit out of it.

The film asks the question, how much will we, as a viewing public, be able to remain indifferent? When our friends and relatives start dying, will we be able to take a photograph of the moment of their death? To observe and film the death? In the end, will we not get tired or ill from our indifference? Will war as horror not supersede war as adventure? “I’ve never felt so scared and so alive”, says Jessie to her tired mentor Ly, while Joel’s eyes shine unhealthily as he prepares to go to the war zone.

Adrenaline is the driving force that takes war reporters into the kill zone, but it is only a matter of time before they grow tired, their batteries run down, and the disfigured bodies of the dead take away the life in their eyes too.

The Americans have made a rather successful, albeit American, attempt to deal with the issue of war. Ironically, it is the civil war that is being shown, because the Americans, in fact, have neither seen nor smelled war in their own country – the only war they understand is civil war. In one scene, there was an attempt to reflect the Holocaust, in other words, all the horrors that war can lead to, but again, the impression of the film is somewhat diminished when you know that the filmmakers themselves can only imagine what they are talking about in real life. (Dora Žibaitė)